By Alfie Davies, Political Philosophy Editor

Institutional Complicity and Moral Indifference: A Critique of Kantian Ethics

Kantian ethics and internalist ideas of moral indifference fail to deal with the (lack of) actions of individuals and institutions in light of tragedies such as the Holocaust.

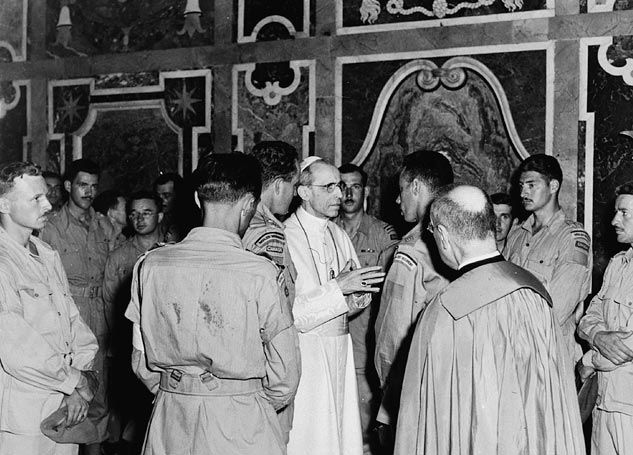

Dietrich Bonhoeffer¹ was one of the first voices raised against Hitler’s persecution of Jews, speaking out in 1933. He declared the Protestant Church must not “bandage the victims under the wheel, but jam a spoke in the wheel itself.”² He hoped the Christian Church would rally together to act against the Nazis. Sadly, not all Christian denominations acted like Bonhoeffer. “The Christian [Catholic] Church … was characterised by fear, avoidance of responsibility… most churches offered little resistance.”³ The Church was “unwilling to risk itself on behalf of the world.”⁴

This failure was not due to any sort of moral ignorance. The Catholic Church was aware of the atrocities happening in Germany. Their awareness is evidenced in an Encyclical letter condemning these atrocities.⁵ They knew, by turning a blind eye, they were doing wrong.

I bring up this case as, not only does it add necessary historical context, but it also asks a poignant philosophical question: “Does it make sense to suppose that a person could judge that one is morally obligated to act in a certain way even though he himself has no (direct) disposition whatsoever to act in such a way?”⁶ Such a view can be called a position of moral indifference, offering a lens through which to view the Catholic Church’s inaction.

As Milo’s essay Moral Indifference points out, the entire concept of moral indifference is debated.⁷ Frankena defines the two competing positions as externalism and internalism; externalism being the position “that it is in some sense logically possible for an agent to have or see that he has an obligation even if he has no motivation, actual or dispositional, for doing the action in question…,” while internalism being “that [externalism] is paradoxical and not logically possible.”⁸

This essay will examine this question and investigate how Kantian internalism fails to explain the Church’s Holocaust⁹ inaction, while Shklar’s liberalism of fear reveals how fear and power can create moral indifference, supporting the externalist view. This essay first explains Kantian internalism, then analyses the Church’s inaction during the Holocaust as a case challenging internalist assumptions, and finally shows how Shklar’s liberalism of fear better explains the moral failures of institutions under oppressive regimes.

At this point it is important to frame the internalist approach before it can be critiqued. The internalist believes the externalist position to be logically incoherent as moral obligations are tied to one’s attitude toward said obligation.¹⁰ If one stated “murder is bad” then they must in some way be inclined against murder.

Internalists find their foundations in Kant, “There are no token actions within Kant’s moral theory which are ‘morally good but not required’. Good but not enforceable? Yes… Morally good but not required? – No, that would be a contradiction in terms.”¹¹ Internalism is inherently Kantian as “[t]he strategy of [Kant’s] moral theory is to figure out what our duties are by analysing what duty is…” and “a duty, to begin with, is a practical requirement.”¹² For both the internalist and Kant obligations are ‘requirements’, “There can be no actions that are morally good but not required.”¹³

This tension between moral awareness and inaction shows a crack in internalist logic: it shows that moral judgment can exist without generating motivation, especially when institutional power structures destroy or suppress individual responsibility. This means that the Church’s failure¹⁴ is not just hypocrisy in the ordinary sense — it hints at a deeper flaw in how internalism connects judgment and action.

Contemporary moral philosophers have questioned the coherence of Kant’s moral theory, bringing the internalist framework under scrutiny. Anscombe attacks Kant in her essay Modern Moral Philosophy. Anscombe states:

“Kant introduces the idea of ‘legislating for oneself,’ which is as absurd as if… each reflective decision a man made [were] a vote resulting in a majority… The concept of legislation requires superior power in the legislator.”¹⁵

Anscombe successfully shows how man cannot be a legislative power for himself. She is mocking Kant’s central moral idea, that rational agents give the law to themselves, as logically incoherent. This is damning for proponents of internalism. If man cannot be a legislative force for man, is it logically possible for a person to believe in a moral obligation but have no attitude towards pursing said obligation?

For Anscombe, Kant fails because his theory operates in a vacuum; it abstracts moral obligation from human psychology and motivation. As she puts it, “It is not profitable for us at present to do moral philosophy… until we have an adequate philosophy of psychology, in which we are conspicuously lacking.”¹⁶

The internalist does attempt to incorporate psychology by insisting that moral judgment necessarily entails motivation. However, this assumption reflects an overly rationalistic view of the human mind. It fails to account for the complexity of moral psychology. Korsgaard, a modern proponent of Kant, gives the example:

“Suppose the case is like this: there are Jews in your house and Nazis at the door… you feel morally obligated to risk death rather than disclose the presence of the Jews… Then you might think: why should I risk death in order to help preserve the species¹⁷ that produced the Nazis?”¹⁸

Korsgaard is acknowledging that moral normativity needs more than just reason. This is where internalist and modern Kantian ethics break away from Kant’s own moral framework. Her example shows that faced with evil the internalist belief in moral obligation equalling motivation breaks down. Kant’s duty model can’t carry the moral weight of history. However, even internalism’s nuanced version struggles in both extreme real-world contexts and in answering Anscombe’s critique of moral self-legislation.

History mirrors Korsgaard’s vulnerability. “Had the railwaymen engaged in strikes or sabotage or simply vanished, there would have been no Auschwitz.”¹⁹ The historical evidence against the internalist position mounts, showing moral awareness does not guarantee action. In this part of my essay, I will show how social and political structures overrule internal moral motivation, allowing for the externalist position of moral indifference.

Shklar’s liberalism of fear is a stark contrast to Kantian duty-based models. While Kantian ethics assumes morality stems solely from reason, for Shklar moral indifference is not logically impossible but a logical reality. Living in fear — of the state, persecution, or oppression — undermines moral agency, especially the fear of state-sanctioned violence or discrimination.

This aligns with her core principle:

“every adult should be able to make as many effective decisions without fear or favour about as out as many aspects of her or his life.”²⁰

Shklar shows that our moral actions are not made in a void; they are shaped by power structures that weaponize fear. “Cruelty is aimed at a particular set of citizens… its infliction will necessarily and deliberately have the effect of preventing them from doing just that [pursuing their life].”²¹

In the context of the Church, Catholicism as an institution feared the reaction of the Nazi government, which was one of the reasons for its muted response to the Holocaust. While the Church may have believed in a moral obligation to resist genocide, its institutional fear of Nazi reprisals paralyzed its ability to act.

Shklar’s argument is supported by historical accounts of Nazi retribution of German catholic dissenters. Adalbert Probst the leader of the Catholic Youth was killed in the night of the long knives.²²

While Shklar’s analysis rightly highlights an attractive alternative to Kantian internalism, her focus on institutional fear risks neglecting historical examples of individuals and groups who weren’t stunned by institutional fear. By comparing Shklar’s liberalism of fear to Arendt’s writings on the Holocaust, we can see that neglecting historical examples of individuals and groups who weren’t stunned by institutional fear is a credible critique of Shklar’s focus on institutional fear.

Arendt writes extensively on the possibility of non-participation, even under totalitarian regimes. While she would agree with Shklar that active resistance was not always feasible, she highlights cases where intentional inaction itself functioned as a deliberate form of resistance. Arendt differs from Shklar, arguing, “There existed the possibility of doing nothing. And in order to do nothing, one did not need to be a saint,” even under the threat of immediate extermination; collaboration was a choice.²³

Arendt agrees with Shklar on the danger of institutional indifference but, like Kant, frames complicity as a failure of moral judgment rather than a consequence of weaponized fear.

Arendt supports her own thesis with the historical evidence of Denmark. She writes:

“Almost half the Danish Jews seem to have remained in the country and survived the war in hiding,” because “In marked contrast to Jewish leaders in other countries, [the Danish Jewish leaders] had then communicated the news openly in the synagogues… ‘all sections of the Danish people, from the King down to simple citizens,’ stood ready to receive them.”²⁴

Arendt successfully shows how her example of Danish Jews surviving due to collective non-participation in Nazi policies from the Danish population, proving that fear wasn’t always determinative.

However, Shklar does not insist fear always precedes moral decision-making. While Denmark is a token example of resistance despite fear, the Netherlands exemplifies the opposite pattern of compliance — with even Arendt conceding that “With the aid of the Jewish council, the deportations from [Dutch] provinces proceeded without a hitch.”²⁵ Instead, fear is simply one of many factors of moral psychology that must be considered when we analyse how agents make moral decisions.

While Arendt correctly compels us to take judgment into account in a moral analysis of complicity, Shklar productively critiques Kant and survives Arendt by showing that such judgments are often clouded by conditions that moral philosophy cannot ignore.

Shklar’s critique of Kantian ethics reveals a central tension in moral philosophy: the danger of abstracting victims and perpetrators into metaphysical concepts. Kantian internalism is innately solipsistic as any ethical model which divorces obligation from lived, social, political context risks over rationalising an agent.

Separating concepts from lived experience is dangerous, Bajohr shows this in regard to the victim. “the consequence of a metaphysical concept of the victim is to reject not ‘mere’ violence, but… reasoned violence.”²⁶ By divorcing the victim from lived experience we condemn only the most obvious brutalities, moving the victim from a person to an ultimate moral principle. The same is true for Kantian ethics. Moral abstraction can mask complicity. This challenges Kantian internalism’s faith in rationality as sufficient moral motivation as Kant believes moral awareness is necessarily followed by action.

The idea that institutions, like the church, can remain neutral in the face of injustice is itself a “refined political ideology.”²⁷ The Church’s adherence to Nazi rule was not based on moral restraint, but a lack of moral action from a subject who is aware of what is right and what is wrong. This is moral indifference – a political choice made under fear.

Shklar’s critique shows the unintelligibility of institutional neutrality. This aligns with her broader critique of Kantian ethics, which, by abstracting moral duty from lived experience and power structures, risks legitimizing passive complicity. Just because Kant believes “[legal separation of law and morals] is desirable,” does not mean “it is also logically necessary or conceptually possible.”²⁸ Hence lived power structures must be considered when talking about moral indifference.

In conclusion, it is evident that Kantian ethics and internalist ideas of moral indifference fail to deal with the (lack of) actions of individuals and institutions in light of tragedies such as the Holocaust. By contrast, Shklar’s liberalism of fear shows that fear and power structures can paralyse moral agency, making moral indifference not a logical contradiction but a social and psychological reality. Shklar allows us to partially understand moral psychology’s role in diagnosing (rather than merely condemning) moral indifference, reminding us that abstract moral theories cannot ignore the concrete conditions that shape human action. Her differences with Arendt show moral judgment can persist despite fear, however cases like the Netherlands show us this is a rarity instead of the norm. In recognising the externalist position and its complexities we gain a more honest and useful lens for confronting moral indifference today.

Bibliography

- Reynolds, D. The Doubled Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Women, Sexuality, and Nazi Germany. Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2017. Note: Reynolds highlights Bonhoeffer’s ecumenical hope for joint Protestant-Catholic resistance, clarifying that his use of “Church” was not limited to Protestantism.

- Bonhoeffer, Dietrich, and E. H. Robertson, eds. Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Selected Writings. London: Fount, 1995.

- Gavin, S. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Christian Resistance and Ethics in Nazi Germany: What Is the Significance of Bonhoeffer? BA dissertation, University of Canterbury, 2014.

Hauerwas, Stanley. “Dietrich Bonhoeffer.” In The Blackwell Companion to Political Theology, edited by Peter Scott and William T. Cavanaugh, 134–147. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004. - Pope Pius XI. Mit brennender Sorge [With Burning Concern]. Encyclical letter. Vatican City: Holy See, 1937.

- Milo, Ronald D. “Moral Indifference.” The Monist 64, no. 3 (1981): 373–93.

- Milo, Ronald D. “Moral Indifference.” The Monist 64, no. 3 (1981): 373–93.

- Frankena, William K. “Obligation and Motivation in Recent Moral Philosophy.” In Essays in Moral Philosophy, edited by A. I. Melden, 40–81. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1958.

- Jones, A. “Genocide.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, 2021.

- Milo, Ronald D. “Moral Indifference.” The Monist 64, no. 3 (1981): 373–93.

- Timmermann, Jens. “Good but Not Required? — Assessing the Demands of Kantian Ethics.” Journal of Moral Philosophy 2, no. 1 (2005): 9–27.

- Velleman, J. David. Kantian Ethics: Introduction. New York: New York University, 2009.

- Timmermann, Jens. “Good but Not Required? — Assessing the Demands of Kantian Ethics.” Journal of Moral Philosophy 2, no. 1 (2005): 9–27.

- Author’s note: This essay does not attempt to answer the question “did the Church have a moral obligation?” Instead it focuses on “if they did have such an obligation and ignored it, why?”

- Anscombe, G. E. M. “Modern Moral Philosophy.” Philosophy 33, no. 124 (1958): 1–19.

- Anscombe, G. E. M. “Modern Moral Philosophy.” Philosophy 33, no. 124 (1958): 1–19.

- Korsgaard, Christine M. The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Note: Korsgaard’s use of “species” refers to humanity as a whole, not specifically the Jewish people. She raises the question of why one should feel obligated to help preserve humanity if humanity is capable of producing evils like the Nazis.

- Korsgaard, Christine M. The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Fackenheim, Emil L. “The Holocaust and Philosophy.” The Journal of Philosophy 82, no. 10 (1985): 505–14.

- Shklar, Judith N. “The Liberalism of Fear.” In Political Thought and Political Thinkers, edited by Stanley Hoffmann, 3–20. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Spencer, Philip. “‘Putting Cruelty First’: The Summum Malum, Genocide, and Crimes against Humanity.” In Genocide and the Idea of Humanity: Writing on the Holocaust, Genocide and Crimes against Humanity, 180–196. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Lewis, Brenda R. Hitler Youth: The Hitlerjugend in War and Peace 1933–1945. MBI Publishing, 2000.

- Arendt, Hannah. The Jewish Writings. Edited by Jerome Kohn and Ron H. Feldman. New York: Schocken Books, 2007.

- Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Rev. and enl. ed. New York: Penguin Books, 2006.

- Arendt, Hannah. The Jewish Writings. Edited by Jerome Kohn and Ron H. Feldman. New York: Schocken Books, 2007.

- Bajohr, H. “The Equivocal Use of Power: Judith Shklar’s Critique of Hannah Arendt.” The Review of Politics 83, no. 1 (2021): 85–107.

- Moyn, Samuel. “Judith Shklar versus the International Criminal Court.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 4, no. 3 (2013): 473–84.